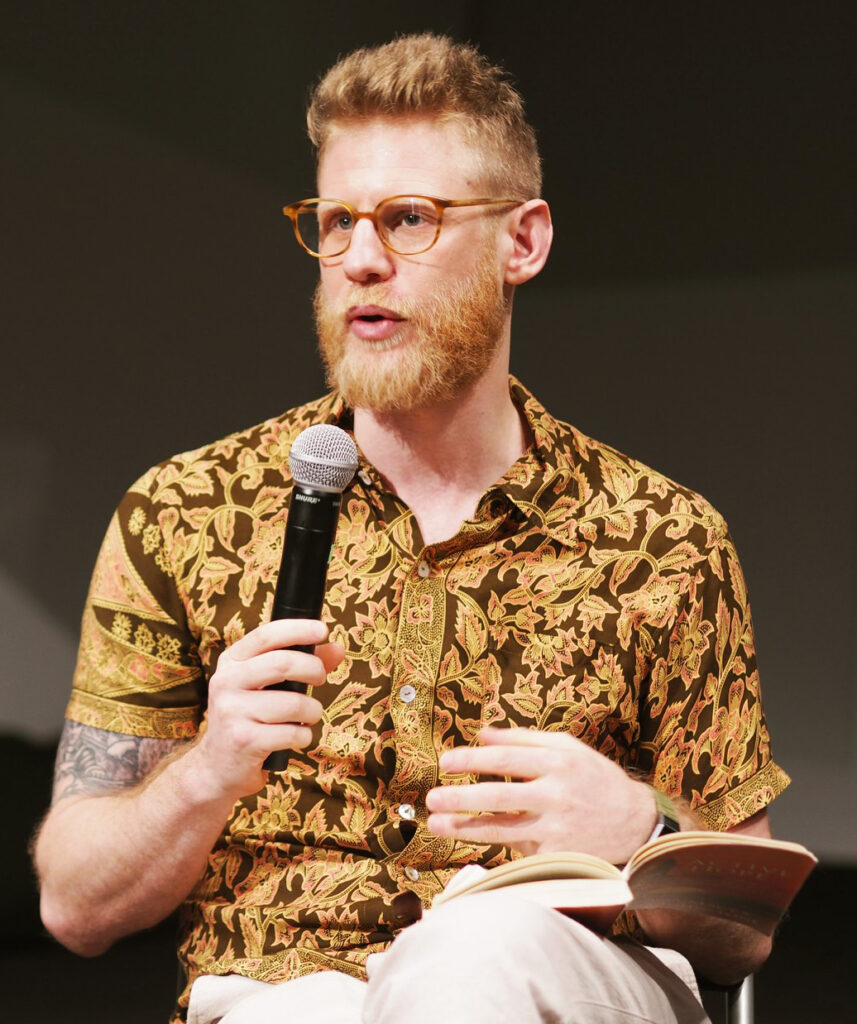

ASLE’s Scholar of the Month for October 2021 is Matthew Schneider-Mayerson.

Matthew Schneider-Mayerson is Associate Professor of Environmental Studies at Yale-NUS College. His research and teaching combine literary criticism, cultural studies, and sociology to examine the cultural and political dimensions of climate change, with a focus on climate justice.

Matthew Schneider-Mayerson is Associate Professor of Environmental Studies at Yale-NUS College. His research and teaching combine literary criticism, cultural studies, and sociology to examine the cultural and political dimensions of climate change, with a focus on climate justice.

How did you become interested in studying ecocriticism and/or the environmental humanities?

I started my PhD in American Studies in 2007 and became interested in writing about the expectations, anxieties, and desires around peak oil, which were remarkably common in the late 2000s. I’d been deeply concerned about climate change for years, and those feelings grew after I read Elizabeth Kolbert’s climate reporting in The New Yorker (which became the book Field Notes from a Catastrophe) and did more research on energy, climate change, and politics. I wanted to write about the peak oil phenomenon from an environmental perspective, and I came across these brilliant scholars that were starting to write about energy from a literary, cultural, and material angle – Stephanie LeMenager, Imre Szeman, Matthew Huber, Timothy Mitchell, and others. I’ve always been interested in the connection between art, culture, and social change, and examining that relationship through the lens of climate change felt important and necessary. I attended my first ASLE conference in 2013 and have felt at home in this community ever since.

Who is your favorite environmental artist, writer, or filmmaker? Or what is your favorite environmental text? Why?

The weight of picking just one anything is too much for me to bear, so I’ll mention two favorites that deserve more attention. I’ve taught The Man with the Compound Eyes by Wu Ming-Yi multiple times in my introductory “Foundations of Environmental Humanities” course, and I appreciate it more each time. Set in Taiwan, it’s a sprawling, polyphonous, eclectic novel that addresses a lot of topics that are central to the environmental humanities, including indigeneity, nonhuman animals, animism, activism, plastic pollution, sea-level rise, epistemology, and imagination. Wu is just incredible.

And ever since I was able to place Here by Richard McGuire into the second half of our first-year Literature and Humanities common curriculum module at Yale-NUS College, my affection for it has only grown. It’s a graphic book presenting the view from a fixed location and perspective over billions of years, including the future. The way that Here plays with our sense of time, narrative, place, and identification is really unique, and it’s a visually stunning, witty, intertextual, and surprisingly fun book – all without having a single named character. A really refreshing and provocative complement to traditional narratives.

What are you currently working on?

I’ve just finished co-editing a foundational collection of empirical ecocriticism, and I’m planning some more experiments on the reception of climate fiction. That’s one of the main ways that I see myself contributing to ecocriticism and the environmental humanities right now – working collaboratively to develop a subfield that brings together research from the environmental humanities and social sciences so that scholars, critics, authors, and cultural workers can have a better sense of what happens when environmentally-engaged narratives encounter actual audiences.

I’m trying to do more public writing, such as an opinion piece on the need to teach climate change with attention to emotion and pathways to collective action, and a short analysis of environmental justice activism in the TV show Ted Lasso. Given the urgency of climate change and other issues, I think it’s important for environmental humanists to contribute to public discourse when we can.

And I’m writing a monograph on the psychological, ethical, cultural, and political dynamics of deciding whether to have children in the shadow of the climate crisis. This is partially a sociological book, based on a large and detailed survey of people that are factoring climate change into their reproductive plans and choices, but it also draws on environmental history, literature and film, environmental ethics, multispecies kinship, queer futurity, and other topics that are familiar to ecocritics.

What is something you are reading right now (environmental humanities-related or otherwise) that inspires you, either personally or professionally? Comment briefly on why or how it inspires you.

I’ve been reading a lot of bell hooks recently, and I was really moved by All About Love, a meditation on different conceptions and forms of love. The way that hooks weaves popular psychology and self-help literature into a radical and accessible critique of the expectations, values, and tendencies of the culture of “white supremacist capitalist patriarchy” is so insightful and compelling. It has me thinking about how everything I do, including teaching, research, and service, can be tied more directly to the things, people, and communities that I love.

And in the wake of the sudden announcement that the thriving institution I’ve helped build for the last six years will be shut down, I’ve been thinking about what I can assign to help our students process, make sense of, and grow from this experience. I’m rereading The Rings of Saturn by W.G. Sebald, a dreamlike, lyrical, genre-defying book loosely organized around a walking tour of Suffolk, and, somehow, silk. Sebald’s books have been treasured companions since I encountered them two decades ago, and I always find them to be a source of wisdom on the passage of time, cultural devastation, injustice, and memory.

Is there a scholar in the field who inspires you? Why?

There are so many people whose work inspires me – Jeffrey Jerome Cohen, Rob Nixon, Joni Adamson, David N. Pellow, Dominic Boyer, Heather Houser, and Bethany Wiggin, to name a few – but I don’t know if I could pick one person as a lodestar. I’ve been involved in a wide range of projects in the last few years, from empirical ecocriticism to An Ecotopian Lexicon to Eating Chilli Crab in the Anthropocene, but what unites them is a sense of experimentation in the search for more effective and just cultural and political narratives that might inspire, guide, and support us through this extended period of socio-ecological violence, turbulence, and transition. So I tend to be inspired by people that are also experimenting – whether it’s with new or mixed methodologies, public-facing projects, working with activists or frontline communities, or building new institutions. I suppose creativity, commitment, and community inspire me. To me the field is stronger, more vibrant, and more impactful when it’s more diverse, more collaborative, and more connected to the real-world struggles that fuel the work we do.