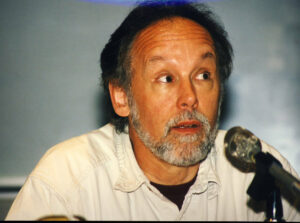

Barry Lopez passed away on Christmas Day, 2020, and will be mourned and missed by many. We have invited some members of the ASLE community who knew Lopez to share their memories of him.

In addition, the editors of ISLE: Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and Environment have collated several articles that have appeared in the journal over the years and created a special feature on the ISLE website: https://academic.oup.com/isle/pages/barry-lopez-tribute

Terry Tempest Williams

“The Color of the River is Light”

Barry Lopez once showed me how to drive the back roads at night with no headlights. Why? I asked. “So you can learn to see in the dark like animals do and not be afraid.” He was disarming. Playful. Beyond serious. Demanding. At times, exhausting. Always, illuminating. And like all writers, sometimes self-absorbed. I loved him. I believe he taught me to see the world differently. I cannot believe he is gone. Now where do I look?

Before he was a writer, he was a photographer. A good one. In fact, the cover of “River Notes,” his collection of short fictions based on his own experience of living along the McKenzie River was taken by him. It is a soft-focus rush of river met by a pair of moccasins placed on a rock facing the water. A credit is given inside the flap of the book: Western Sioux moccasins courtesy of the Lane County Museum, Oregon. The composition is studied and deliberate, aesthetically pleasing and evocative like each of his stories with a flare of magic.

On the back of the book that measures 8 3/4” x 5 3/4” with a mere 100 pages, is a horizontal strip of four black and white photographs of the author, reminiscent of the four flashes of pictures one would spontaneously pose for inside a photo booth with friends. The first shot is Barry looking down, with his index finger resting vertically on his upper lip, the tip of his finger just below his nose. He is deep in thought; the second frame shows him looking upward, his eyes glancing to the right; the third frame is a straightforward gaze, direct; in the last frame he is looking down, slightly toward the left. Had their been a fifth frame taken some time before his death on December 25, 2020, I imagine his eyes would be closed, his head in a slight bow with his two hands pressed together in prayer.

In our long, deep and complicated friendship, I came to rely on his varied moods of mind and heart. I believe part of his genius as a writer was rooted in his access to the extremities between his vulnerability and strength; his knowing and unknowing, call it doubt; and the exquisite arc of revelations created from the depth of his searing intellect to what some critics saw as the naiveté of his beliefs in Nature. In truth, this is where the urgency and wisdom of Barry Lopez dwelled. His hunger to understand the roots of cruelty was located in his wounds. His longing to believe in our species was housed in his faith. When my grandmother died, I gave Barry her silver cross with a small circle of turquoise placed at its center. His obsession with god and the power of our own creativity landed elegantly on each page he wrote, be it his fascination with the intricacies of a ship or plane or an imagined community of resistance where people took care of one another in the midst of darkness. Very little escaped his closely set eyes. Barry was the Michael Jordan of environmental writing and when my father gave us his tickets to see the1987 NBA championship game between the Chicago Bulls and Utah Jazz, Barry never spoke, he was transfixed on Jordan’s every move with his game stats on his lap. Barry brought this same kind of intensity to every occasion. His fidelity was to his work where his devotion to language and landscape gave birth to stories.

Barry taught me early on that the color of the river is light. For him, the river was the McKenzie that fed his life force for fifty years where salmon spawned each year in the shallows in the Blue River Valley just outside Eugene, Oregon. As an exercise, he would often put on his waders and walk across the river as the mergansers would swim around him.

In 1983, I first visited Barry and Sandra, the artist he was married to for thirty years, at their enchanted home in Finn Rock. Sandra offered me my first cup of coffee on their porch. Coming from the arid country of Utah, I had never seen such lushness, the delicacy of ferns, yews, and the density of alders below the Douglas firs and red cedars that drew your eyes upward toward a hidden sky. In that moment, I recognized our differences, he was a man of the trees and I was woman of the desert. Our friendship grew from what was hidden and what was exposed. We pushed each other, challenged each other, and we relied on one another’s perceptions.

Barry and I met in 1979 in Salt Lake City when he came to read at the University of Utah, paired with Edward Abbey for a special fundraiser for the Utah Wilderness Association. Two thousand people came to hear Cactus Ed court and cajole dissident behavior. He did not disappoint. People howled like coyotes after he finished. When the next speaker stood up on stage, few had heard of Barry Lopez. But after he read from “River Notes,” with his deep, sonorous voice, a great and uncommon silence filled the ballroom. No one wanted to leave. A spell had been cast by a Storyteller. We left the reading altered, recognizing we had not only heard a different voice, but a voice that offered a forgotten language that brought us back into relationship with the sensual world of humans and animals living in concert together.

In his story “Drought,” he showed us how one sincere act born out of love and a desire to help had the power to bring forth rain in times of drought if someone was foolish enough to dance. I would exhort the river, his narrator said.

With no more strength than there is in a bundle of sticks, I tried to dance, to dance the dance of the long-legged birds who lived in the shallows. I danced it because I could think of nothing more beautiful. And with a turn of his page, we learned, A person cannot be afraid of being foolish. For everything, every gesture is sacred.

In Utah, we knew irreverence from a writer like Ed Abbey that inspired the antics of the Monkey Wrench Gang. What we had not heard before on that landmark night, was a writer evoking reverence.

The next day, I drove Barry back to the airport located near Great Salt Lake. Curious, he asked me questions about the inland sea. I must have gotten lost in my enthusiasm about the lake, how it was our Serengeti of birds with avocets and stilts, ruddy ducks and terns, how one could float on one’s back and lose all track of time and space and emerge salt-crusted and pickled, and how the lake was a remnant puddle from the ancient Lake Bonneville whose liquid arm reached as far west as Oregon 30,000 years ago. Before Barry boarded the plane, he turned to me and said, “I exhort you to write what you know as a young woman living on the edge of Great Salt Lake.”

There was that word again, exhort I went home and looked it up: “to strongly encourage or admonish….” It was a biblical word, “a 15th-century coinage derived from the Latin verb hortari, meaning “to incite,” and it often implies the ardent urging or admonishing of an orator or preacher.”

Barry Lopez had given me an assignment. I took his assignment seriously.

For more than forty years, I have known that wherever Barry Lopez was in the world whether he was kneeling on the banks of the McKenzie River awaiting the return of the salmon or watching polar bears standing upright on the edge of the Beaufort Sea in the Arctic to flying his red kite in Antarctica with unbridled joy, the world was being seen by someone who dared to love what could be lost, that he was listening to what could be silenced and was finding an intimacy with — rather than a distance from — the ineffable. In those luminous moments, he would find the exact words to describe what we felt, but didn’t know how to say. He exhorted his readers to pay attention through love.

The last time we were in Jackson Hole after a pause in our friendship, we stood on top of Signal Mountain facing the Teton Range. It began to snow with goose down flakes in full sunlight and a clear blue sky. He looked up and said, “Well, I’ve never seen this before.”

Barry Lopez’s very presence incited Beauty. Even as his beloved trees in Finn Rock burned to ash in the fires that engulfed the Blue River community in the fall of 2020, his eyes were focused on the ground in the name of the work that was now his — “the recovery and restoration of Finn Rock,” the phrase he used in our last correspondence, even as he understood what was coming. In one of his last essays, “Love in a Time of Terror,” he wrote, “…in this moment, is it still possible to face the gathering darkness, and say to the physical Earth, and to all its creatures, including ourselves, fiercely and without embarrassment, I love you, and to embrace fearlessly the burning world?

Grief is love. Barry Lopez was surrounded by the love of his wife Debra Gwartney and their four daughters at his death. His love in the world remains.

Everyone has to learn how to die, that song, that dance, alone and in time….To stick your hands in the river is to feel the cords that bind the earth together in one piece.

Peace, my dear Barry. The color of the river is light. You are now light. Hands pressed together in prayer. We bow.

Scott Slovic, University of Idaho

Barry Lopez always seemed larger than life when I was a young ecocritic in the late-1980s, working on my Ph.D. dissertation (including a chapter on Arctic Dreams, which had just won the National Book Award) and beginning to teach environmental literature and writing, often using Barry’s works as readings for my students. I first met Barry in person when John Tallmadge, the president of ASLE at the time, organized a small lunch gathering in the cafeteria at the University of Montana during the June 1997 ASLE conference. In addition to Barry, John, and me, I recall that Barbara Ras, David Abram, and my son Jacinto were there. What I remember most vividly from that first meeting were Barry’s antic tales about practical jokes he’d participated in during various outdoor adventures, some of them involving inflatable alligators. While Barry shared comical stories, magician and philosopher David Abram used sleight of hand to move fruit and other items from plate to plate on the table. I remember my son, then about ten years old, approaching Barry later in the hallway during the conference and asking him to autograph his shoes—this was during basketball player Michael Jordan’s heyday, so of course Barry wrote “Airy Lopez” on Jacinto’s sneakers.

Over the years I came to know Barry as not only an extraordinary writer and a kind and funny person, but as someone deeply interested in supporting fellow artists and scholars. Whenever I wrote to Barry with questions about his work, he responded with lengthy letters of explanation. I had the opportunity to witness his generosity at the ASLE gathering in Missoula and later at the Orion Society’s Fire & Grit Millennial event in West Virginia and another time when he came to visit us at the University of Nevada, Reno, in 1999. In December 2019, Barry attended my graduate seminar on Geographies of Nonfiction at the University of Idaho via Zoom to talk about his new book Horizon, and we had an unforgettable conversation with the students about the aesthetics and ethics of travel and travel writing. At that time, he mentioned that his doctors had advised him that his days of travel—after decades of global wanderings—were over, so he was planning to redirect his attention to the mycelial network growing underground at his home near the McKenzie River, east of Eugene, Oregon. It was deeply distressing to learn this fall that the Holiday Farm Fire had sent his writing studio and a lifetime’s worth of manuscripts and memorabilia up in smoke. This is a season of loss. The community of ecocritics and environmental writers and activists will miss Barry’s companionship and mentorship, but we’re lucky we can carry his wisdom with us in the form of his many books, essays, and stories—and in other ways.

This morning a friend from the McKenzie River Trust in Eugene lent me her copy of Barry’s 2016 limited edition volume Life on the River, written in support of the Trust. Early in the book, Barry tells the story of traveling to meet a mountain lion biologist in Arizona, who reveals to the visiting writer that what he knows about the lion is “here” (in his chest), “not in here” (pointing to his head). Barry then states: “That’s how I feel about the McKenzie River. It’s in here [points to heart]. I’ve lived on the north bank of the river, near Finn Rock, in the same house for forty-six years….” This is how I feel about Barry Lopez and his luminous words and ideas. They live in here (pointing to my heart), not in my head or in books and articles. I have the sense that many ASLE friends and colleagues feel the same.

Priscilla Solis Ybarra, University of North Texas

“On Barry Lopez and Storytelling for Our Community”

In April 2017, Barry Lopez agreed to give the Inaugural Annual Lecture for the Leopold Writing Program, a non-profit in Albuquerque for which I now serve on the Board. The Board thought it would be inspiring for the grades 6-12 winners of the Program’s Annual Writing Contest to hear a writer of Barry’s integrity and renown lecture and to receive their awards from his hands. Seeing the next generation of writers on stage with Barry was more than worth my drive from North Texas to be there. Barry wrote an original lecture for the occasion, invoking Aldo Leopold, discussing the unique cultures of New Mexico, and drawing our attention to the strength forged through maintaining different cultures alongside one another, even in the face of the difficulties that sometimes presents.

I found these aspects of his lecture, discussing human cultures, social justice, and the environment, particularly compelling:

“In my travels to different parts of the world, to Australia where I’ve traveled with Aboriginal people on their lands, in the Canadian High Arctic where I have traveled with the Inuit, I have been repeatedly struck by the same thought: if we are coming into a time of extreme environmental stress and of extreme social tensions, why is it that so few people who have actually dealt with these problems are invited to the table for the discussion? We know why. Here are the questions of race, of cultural superiority, of patriarchy, of educational bias, of religious conviction, that cripple us when our effort is simply to care for our families, our progeny.”

and then later in the lecture:

“If we’re going to survive and to thrive in whatever landscape the world offers us in the decades ahead we must learn to speak respectfully to each other, to listen to each other, to take into consideration the fate of each other’s children. That is what Leopold was saying; it’s what he saw in the eyes of the dying wolf, the wolf was saying, ‘Wake up! Wake up.’ The Aldo Leopold Writing Program, the essay contest that has brought us together today, … all have the same aspiration: to awaken us to the beauty and the inevitability of a multicultural existence. I would go so far as to say: to awaken us to the salvation of a multicultural existence.”

This tenet—that justice and respect for traditional cultures is at the center of our endeavors to maintain a planet both beautiful and human-sustaining—was at the core of Barry’s work, Barry’s life. It was also at the core of my friendship with Barry. While readers and critics made the most of Barry’s descriptions, experiences, and insights of the natural world, the heart of my conversations with him was how traditional cultures and the pursuit of justice shaped his view of the natural world. It’s what we talked about around a conference table when I first met him in 2006 when I was a new Assistant Professor at Texas Tech, and it’s what we talked about throughout the annual Sowell Conferences—a gathering organized at Texas Tech to celebrate the writers in the Sowell Collection archive that includes Barry’s papers. The October 2019 conference was the last time I saw him.

During our last conversation, when we found a few minutes to sit in a quiet corner away from the boisterous after-conference gathering, I asked him to repeat for me one of my favorite stories that I heard him tell. It’s the one about trying to explain to an Aboriginal man in Australia the kind of writing that Barry did—creative non-fiction. The distinction between fiction and non-fiction did not add up to anything meaningful to the Aboriginal elder that Barry was talking to. Instead, the elder offered Barry another way to understand stories: authentic versus inauthentic. The authentic story is about us, the community, while the inauthentic story is about the individual telling the story. That’s it. And it’s just about the best advice, about storytelling and about how to live, that I’ve ever heard.

Our conversations for over a decade, and our respective careers, were focused on working at the same knot of culture, justice, and the environment. I got to see him a couple times a year, even after I left Texas Tech—working with students, speaking at conferences, debating with faculty reading groups. Barry mentored me throughout my entire career as a professor in ways that I never fully recognized until now. You’d think that would have been obvious to me, but Barry was subtle about things like that. It wasn’t about me, and it wasn’t about him. It was about the community he was nurturing. For all of his beautiful work, and for his generosity and grace, I’m so deeply grateful.

I’m proud and honored to call him mentor and friend, and to have also shared some laughs with him. He had such a mischievous sense of humor. I’m really going to miss Barry. But I get the feeling he’s already doing okay on the other side, and even having fun with it. It’s going to be interesting to see how this goes with him over there and us still over here.

John Lane, Wofford College

I will always think of my departed friend Barry Lopez as one of the spiritual tent pegs holding down the big tent of ASLE. Barry was a plenary speaker at the first conference I attended—in Missoula in 1997. I remember him reading outdoors near the river and then us talking afterwards about the years since we’d seen each other. I also had lunch with Barry and others in 2005 in Eugene, when the conference was close to his home on the McKenzie River. Both times Barry wandered among us—giving, interested, engaged. His work has also been evoked in numerous papers through the years. How many, I don’t know, but I know it’s a bunch.

Barry was a friend and mentor for forty-one years. When I think of him, I always remember pressed shirts and jeans, though other friends remember Carhartt pants and fleece jackets and his ubiquitous ball caps. Barry always seemed put together in public. What he said in public or in private asides was always considered and put together too, his speech as elegant and timeless as his orderly and simple western clothing. I also remember a little glint of turquoise—which always reminded me of the startling lyric patches of his nonfiction and the clear quartz focus of his friendship.

On my bookshelf I have a poem of Barry’s in a stitched, orange pamphlet called “Desert Reservation,” in an edition of 300 copies published by Copper Canyon Press in 1980, a wry, four-page indictment of what I take to be the Desert Museum in Tucson. It’s a place about which the speaker has “heard so much good,” but when he visits, he sees the animals have all gone crazy in their cages and pits. “Only Coyote doesn’t seem to care, asleep under a/creosote bush, waiting it out.”

How much poetry did Barry write? Maybe some scholar knows, but I imagine part of the answer went up in flame and smoke when his archive shed burned in the Holiday Farm Fire on the McKenzie River in September, a blow and tragedy that I am sure contributed to the quick collapse of his fragile health this fall.

I have three or four more of these fine press pamphlets with bits of Barry’s prose in them. Of these, my other favorite is “Pulling Wire,” a story I don’t think he published anywhere else except in this 2003 pamphlet with 240 copies from Red Dragonfly Press. It’s the story of a retired logger, about the age I am now, who salvages metal off old logging sites and has an encounter with a bear performing a similar task who drops an “eight-inch head bolt” into the old man’s truck bed.

These are rare and beautiful publications, the kind of printing Barry loved so much. The sort of care that fine press printers take is something as wild and threatened as the Arctic animals Barry documented in Arctic Dreams. These ephemeral publications form an intimate lasting legacy in sharp contrast to his big mass markets books.

Reading these little pamphlets this morning helps me assuage my grief. Barry’s words—and the beauty of the printing—build up strength that what we love well does remain.

Somebody will open up these pamphlets printed on acid-free papers many years from now in the ugly aftermath of our present age and wonder how it was in the not-so-deep past that language and experience could have been given such elegant and respectful presentation.

So, this morning I read Barry’s words in remembrance. Barry’s wife Debra Gwartney and his loving family have committed his earthly body to fire and released his spirit to walk what his friend Gary Snyder has called “the spirit path in the sky,/ that long walk of spirits.”

But Barry is not gone—to me or to ASLE. Barry lives on in his work. As a gesture as prayerful as his bowing to the tundra birds in Arctic Dreams, I place these beautiful artifacts back on my special shelf until the next time I need him.

Diane Warner, Southwest Collection/Special Collections Library, Texas Tech University

I first met Barry Lopez at the 2000 Texas Book Festival in Austin. My husband and I listened to Barry’s talk, then stood in a very long line in the book signing tent. As Barry returned our book to us, he looked directly and warmly at both of us, and said, “Take care of each other.” I now know Barry said that many times to many people, a mantra to remind us of our place in a community. If I only learned one thing from Barry, let it be the sacredness of our responsibilities to and relationships with others.

At Texas Tech, I’m the librarian working most closely with Barry’s archives. This was my great good fortune, not only because Barry was an archivist’s dream donor, but because through the years he became my friend and mentor. As his own archivist, Barry was very meticulous. In 2019, we received the most recent update to his papers. Everything was packed in clearly marked boxes, separate items already housed in archival folders, labeled in Barry’s distinctive handwriting. Processing this collection, which is underway, will be a simple task, though it is now complicated with our sense of grief and loss.

Whenever Barry came to Lubbock, he’d walk into my office carrying a cup of coffee, wearing his baseball cap and fleece jacket, with that twinkle in his eye that seemed to say “Here we are again. Life is good.” We greeted each other with a hug and a smile, then turned to whatever archival project was in the forefront—new collections, students and classes, our annual conference. We worked together for many years, we also laughed, sometimes he teased me. There is so much to remember and be thankful for.

*************************************

My husband and I drove to the Muleshoe Wildlife Refuge before Christmas, knowing that Barry was quite frail at the time. We’d been there before with Barry, Kurt Caswell, and a group of TTU students. The first visit was full of boisterous and youthful community, sandhill cranes, ducks, long walks around the playas. This time, 2020, it was quiet, no rain for months, the playas dried up, salty, barren, no ducks, no geese. Yet we heard sandhill cranes, heard them over and over, as if they were circling high above us. That magical way you hear them, but can’t see them, and then suddenly, the group turns or shifts and the sunlight catches them just right, so they shine and become amazingly clear.

Kurt Caswell, Texas Tech University

Over the last sixteen years of Barry Lopez’s life, I worked with him in his position as distinguished visiting scholar at Texas Tech University where I am a professor in the Honors College. In that time, Barry and I taught together, led students on field experiences, and supported librarian Diane Warner and the Sowell Collection (where Barry’s papers are housed). We also shared meals at restaurants and at my home, shared stories (so many stories), and got together for movies. He became central to my development as a writer, as a teacher, and as a human being, and he became my friend.

Barry was also a friend to the ASLE community. He was a guide for us, an example, a source from which many of us drew information and inspiration. He was a writer who exemplified ASLE’s mission, and as I see it, was foundational to the formation of the organization. And he will remain so, for we will honor him by reading and writing about his life and work, by gathering for our biannual conferences, and by caring for the earth and each other. I received this instruction from Barry many times: “For god’s sake, take care of each other,” he would say.

I want to tell you one story about Barry.

In the spring of 2014, Barry and I, along with two Comanche friends, hiked a group of students to a stone medicine wheel at the top of the highest of the four Medicine Mounds near Quanah, Texas. These Medicine Mounds are a series of conical hills, each rising some 350 feet off the featureless plains. Comanche people have long known this place for its good water, abundant game animals, and available herbs, and as a place where human beings can communicate with the spirit world. It was a clear, sky-blue day, and the sun was still canted eastward. At the top, our little group broke up to wander about at leisure, and Barry went off by himself to stand near the medicine wheel. Moments later, Barry was striding fast right at me. He threw his arms up over his head, tears coming down his face, and said: “Amazing! Beautiful! The power coming off the top!” Then he wrapped his arms around me in a powerful hug. “I love you, Kurt,” he said.

I don’t tell you this story to claim some special place in Barry’s life, but to make two observations. First, the story illustrates how engaged and moved Barry was while traveling in wild places, moved by the animals he encountered, moved by the way light changes the visible world across the length of a day, moved by the presence of the sacred. And second, the story says something about the way Barry faithfully extended his hand and his heart to the people in his company. He well understood (and so he taught me) that the foundation of human life is the community, not the individual, and each person in a community has a vital role to play. Because it is the collection of voices that makes us human, Barry would say, it is our responsibility to make sure no one is left out. I will be forever grateful for this teaching.

Like you, I will miss Barry Lopez, and miss him deeply. I take some comfort in knowing from his wife, the writer Debra Gwartney, and the rest of the family, that Barry’s passing was gentle, and that he was surrounded by photographs, artwork, and music representative of his extraordinary life, and that he was in the company of the people he loved best.

(Kurt Caswell’s newest book of nonfiction is Laika’s Window: The Legacy of a Soviet Space Dog. He is also the author of Getting to Grey Owl: Journeys on Four Continents, and In the Sun’s House: My Year Teaching on the Navajo Reservation. He teaches writing, literature, and outdoor leadership in the Honors College at Texas Tech University.)

Clinton Crockett Peters, Berry College

Do you remember the Red Sox breaking a curse? I sat in a parrot-themed bar with pumpkin-sized margaritas, Barry Lopez, and faith-keeper of the Haudenosaunee Turtle Clan, Chief Oren Lyons. Lyons had given a standing-room-only talk at Texas Tech, and there were scant places to feed afterhours in Lubbock. “The thing is when you become a leader,” Lyons had said, “you have no one to look over your shoulder anymore.”

Across hushpuppies, I tried juicing the two titans for meaning. They wanted to watch baseball. Seven screens lit up red eyes. Both were exhausted from travel, students, speaking. Lopez brushed off my concern about coming from nowhere. “This isn’t a bad place to write from,” he said, “There’s a story in this Llano that needs telling.”

I eyed the margaritas, recalled the dust storms, compared that to the Arctic and Antarctic, and doubted.

Lopez frequented Lubbock, checked on his students, and gifted 75 boxes of flotsam to the university Sowell Collection. I’d scavenged these cartons, tracing a route through blue ink corrections, bags of feathers and whole birds gifted by fans. I’d hoped to trail his success. It is a curse of the young to believe someone else’s life will lead you, to forget that there are many ways up the mountain but that in death, the view is the same.

Lopez once said to me Moby Dick could take place in Lubbock. It wasn’t until I’d finished my second book, a dozen years later, that I understood. Everywhere is epic if you let the land breathe into your syntax. If you unearth fossil metaphors, gaze upon sandstone hieroglyphs, and read the clouds’ calligraphy. We will all be buried upon landscapes that mold us.

I’d always thought I’d speak with Lopez again, talk baseball like a “real” writer, not a punk college kid. But I wish I had him here, glancing over my shoulder, appraising the dust I walk.

John Tallmadge, Independent Scholar and Consultant

I first met Barry Lopez in 1980, when I was teaching at the University of Utah. He and Ed Abbey had been booked for a campus visit and public reading to benefit the Utah Wilderness Association. Abbey was the big draw. Almost no one had heard of Barry, even though he had published Of Wolves and Men and, more recently, River Notes. When Abbey missed his flight, Barry was plugged in for the obligatory lunch with students, where he blew our minds with startling tales of animal power and human transformation.

And the same thing happened that night at the pubic reading. Thousands had come to hear Abbey but left dazzled by Lopez. We all loved Desert Solitaire’s blend of romantic lyricism and countercultural irreverence put to the service of a good cause. But we’d never heard anything like the shamanic magical realism of Barry’s stories. It was electrifying.

Later at the afterparty I watched Abbey presiding over the hors-d’oeuvres, surrounded by fans, while Barry sat on the floor in a corner huddling with students. They made quite a pair, the grizzled patriarch and the intense, dark-haired young prophet. I could sense the passing of some unseen mantle. And a few years later Barry would come out to Carleton, where I was then teaching, and bring the same gifts of wisdom, energy, and generous attention to my classes, both indoors and out in the field. He was great with students, but he later confessed that despite his admiration for both teaching and scholarship, his true place was in front of a typewriter rather than in front of a class.

I especially remember one incident from that visit. It was a warm May night, and we’d booked a ground floor lecture hall. Outside, the ducks were all coming up from the creeks and ponds to nest and brood on campus. Right in the middle of Barry’s reading a cute yellow duckling wandered in, obviously bewildered. We all gasped, but Barry just reached down, picked it up gently, and carried it outside, murmuring comfort. I’d seen that combination of power, respect, and tenderness before, and would see it again in both his person and his writing.

In subsequent years Barry and I would enjoy collaborations through ASLE and the Orion Society. He became “a writer who travels,” exploring remote places, not in search of wealth or power but of stories. Tutored by the land and its inhabitants, he learned to respect both Western science and traditional ecological knowledge. The dignity, resilience, and imagination of native people who live close to the earth struck him as posing a necessary, even vital challenge to our materialistic, self-satisfied culture. He discovered the therapeutic value of landscape and narrative. “The stories people tell have a way of taking care of them,” he wrote. “Sometimes a person needs a story more than food to stay alive.” Few writers have been more attentive to the social obligations as well as the practice of their craft. He liked the Eskimo word for storyteller, isumutaq, which means “one who can create the atmosphere where wisdom shows itself.” And he foresaw the transformative potential of nature writing to “provide the foundation for a reorganization of American political thought.”

Barry was one of our greatest teachers. By word and example he inspired us to do and be our best as scholars, teachers, and practitioners of nature writing. A great light has gone out, but fortunately we are not going to lose the path. Barry Lopez taught us how to see in the dark.

James Warren, Washington and Lee University (Emeritus)

Missoula, Montana, July 1997. On the last night of the second ASLE conference, Barry Lopez gave an open-air reading in Caras Park, on the banks of the Clark Fork. It had been raining in the afternoon, off and on. In the dusk, Barry stood on the pavilion stage and read his tribute to Wallace Stegner, who had died just a few years before. Then he began reading the short story “Lessons from the Wolverine,” a story already known to many in the audience and just printed in an illustrated hardback edition before the conference. The air was still humid, and the sounds of his baritone voice mingled with the rushing of the river. He came to the place in the story where the two wolverines tell the narrator in his dream vision, “Keep going!” But instead of continuing, Barry paused and looked out beyond the audience. Our crowd of five hundred were whispering to one another, looking over their shoulders, as if they were making a collective rustle of wonder. A full double rainbow was vibrating in the skies south of the river. Barry paused another moment, looking out at the double arc and giving his listeners time. “Okay,” he said, “Keep going!”

Many ASLE members will remember that reading or will remember having heard the story. It was a remarkable conjunction of landscape and storytelling, the kind of joyful conjunction that Barry Lopez created in his essays, short stories, and longer works like Of Wolves and Men, Arctic Dreams, and Horizon. The rainbow teaches us, like the wolverine and like the stories Barry tells us: “Keep going!” Barry’s courageous life—the resilience and restraint that marked his ways of meeting repeated losses, traumas, and griefs—teaches us, “Keep going!” Not because we are doomed to endure, but because we live and breathe in a world of pain and wonder.