By Mark Terry

One of the often examined and cited challenges in creating progressive global policy on environmental issues is the real or perceived communications gap between science and policy. Since many policymakers are not scientists but merely elected officials, sometimes it is difficult for them to understand complex scientific reports. Conversely, scientists need to be precise and accurate in the reporting of their methodologies and findings and sometimes have difficulty in presenting this data in a generally accessible manner.

Through my experience as an environmental documentary filmmaker for nearly thirty years, I have had the opportunity of working with both groups and have experimented with several approaches to assist these parties in bridging this communications gap. After ten years of such research and investigation with various digital media and related affordances, I have developed a new form of documentary that I have successfully tested in the field with the United Nations, called the Geo-Doc. I have detailed this research in a new book The Geo-Doc: Geomedia, Documentary Film, and Social Change (Palgrave Macmillan).

Through my experience as an environmental documentary filmmaker for nearly thirty years, I have had the opportunity of working with both groups and have experimented with several approaches to assist these parties in bridging this communications gap. After ten years of such research and investigation with various digital media and related affordances, I have developed a new form of documentary that I have successfully tested in the field with the United Nations, called the Geo-Doc. I have detailed this research in a new book The Geo-Doc: Geomedia, Documentary Film, and Social Change (Palgrave Macmillan).

For environmental humanities scholars and teachers, the Geo-Doc can also serve as a pedagogical tool for both teaching and learning. Geomedia are fast becoming popular educational instruments in secondary and post-secondary institutions. The various location-based technologies can serve as a database of information in various media that students and teachers eagerly use in the classroom. Geomedia also serves the goals of experiential education when students use it as a project to create their own Geo-Doc. In this capacity, students learn a technology for reporting on a global environmental theme but also develop a set of skills that can be applied as a presentation platform for other academic projects that lend themselves to global themes as well as digital and visual delivery. In the afterword of my book, I outline a step-by-step guide for educators to teach and for students to use to create their own Geo-Doc project.

The Geo-Doc can be a valuable instructional tool to showcase global research on environmental issues. It provides a 10,000-foot perspective of any global environmental issue. Rather than just looking at air pollution in the US, for example, the teacher can populate the Geo-Doc project with video and written reports of air pollution research, impacts, and solutions the world over, providing insight into what worked and what failed. This epistemological approach leads the students into a more comprehensive research methodology. If the teacher prepares the Geo-Doc project with all the digital content available – films, photographs, books, research papers, and scientific reports – within each multimedia pin, the project can become a foundational micro library of assets for extended research.

I currently teach a course incorporating the Geo-Doc as a project, ENVS 1010: Introduction to Environmental Documentaries, at York University in Toronto. Students are directed to work in teams of three: a curator, a designer, and a writer/researcher to create a Geo-Doc with a specific environmental theme of their choosing. Here is a description of these roles that I provide to my students:

- Curator: The Curator will collect film units related to the selected environmental theme. Students may also want to shoot their own footage, but it must be uploaded to YouTube for the project.

- Designer: The Designer will upload the film units based on the geographic location of each film segment. For example, if the story takes place in Hong Kong, the Designer will post the video on the longitude and latitude coordinates of Hong Kong. The Designer will also select the pin style and assign colours to categories of their choice (year of production, country of production, etc.).

- Writer/Researcher: The Writer/Researcher will collaborate with team members to identify categories for metadata appropriate for their selected environmental theme. They will then provide content for these metadata categories including links to websites and hyperobjects that offer more information on the film unit’s specific subject.

This experiential educational approach enhances team building and introduces a hands-on technical practice to all three major areas of Geo-Doc creation. The step-by-step guide and the group project enrich the pedagogy of environmental education between teacher and student. This student project on the subject of the sustainability of “fast fashion” production and consumption in seven countries illustrates what the final product might look like.

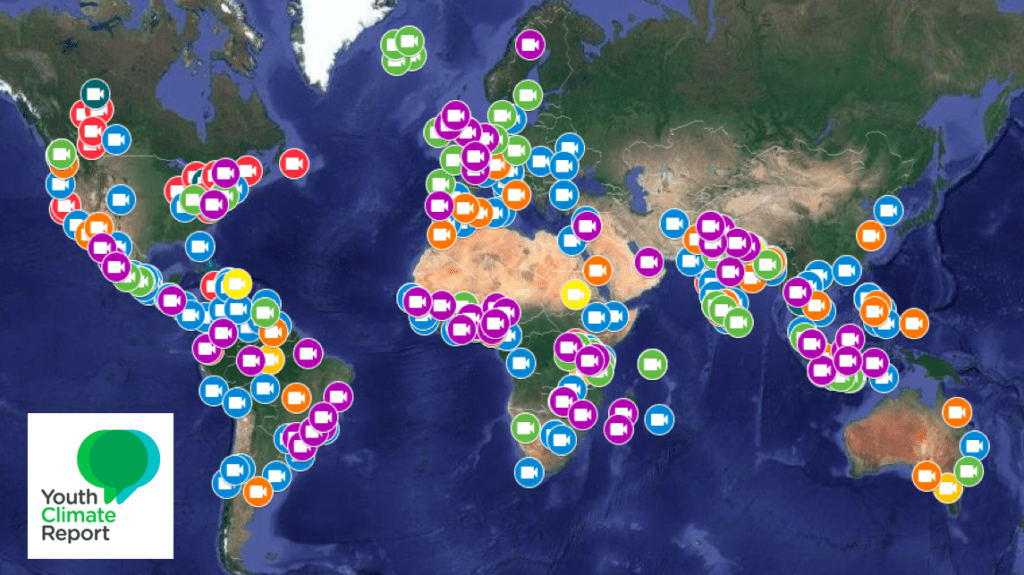

Using an exhibition platform of a Geographic Information System map, the affordances of online technologies allow for a data visualization project incorporating a wide range of multimedia. In particular, multilinear and database documentary film projects and hyperobjects enhance the research data with valuable visual content. This framework was tested in the field with the United Nations at its annual climate summits (known as the COP conferences) with a project called the Youth Climate Report. First introduced in Paris in 2015, the prototype showcased fifty documentary short films on climate research worldwide to the delegates in attendance. The project benefitted from collaborative feedback received directly from the international environmental policymakers who used the Geo-Doc as a data resource during the historic conference. This collaboration helped shape the Geo-Doc so that it did not compromise the scientific rigour of the profiled research and at the same time provided policymakers with visual content that gave much-needed context to the complex text of written scientific reports.

The video content was produced by the global community of youth (aged 18 to 30) who also served as reporters interviewing multinational researchers on their latest climate change data. Since the scientists were reporting to students instead of peers – the common audience of academic papers – they presented the material in a way that was more accessible to the uninitiated; coincidentally, this audience shares a similar comprehension profile with the audience of policymakers. Giving voice to youth also gives this traditionally under-represented group a seat at the table.

Collaboration is key to the success of a project such as this. The Communications office of the UNFCCC assists in the curation of film components with a contest called the Global Youth Video Competition, which they administer together with a UK-based group called Television for the Environment. Each year, these offices (along with the Youth Climate Report through its websites and social media networks) announce climate-related themes and disseminate a call for entries. Other methods of curation include the Planetary Health Film Lab, an intensive, one-week workshop for international young filmmakers offered by York University’s Dahdaleh Institute for Global Health Research in Toronto where specific Geo-Doc training is provided. The workshop provides technical instruction for film production, interview techniques, and Geo-Doc creation in a collaborative think-tank environment. At the end of the week, the three-minute-long projects are premiered at a “micro film festival” before being uploaded to the UN’s Youth Climate Report. The participants are encouraged to return to their home countries and share these skills with their peers to increase active participation in the Global Youth Video Competition and amplify the voice of global youth on the issue of climate change.

A multilinear project such as this is known as a “living” documentary since, unlike a conventional linear documentary, it has no end. New content added each year provides current data through each film’s explicit narrative yet, at the same time, it can provide new data when the film units are compared to each other. The example I like to use is this: if documentary film units examining glacier retreat in the Arctic are related to those made in Antarctica during the same year, we might uncover different rates of decline leading to a discovery that one polar region is warming faster than the other. The explicit narratives of each film do not convey this information, yet when they relate to each other temporally and spatially, implicit narratives – and new data – can be revealed.

This is the basic framework of the Geo-Doc, and to strengthen its communicative power as an instrument of social change for global issues such as climate change, proven documentary theory and practice are invoked as part of the Geo-Doc production methodology: The Participatory Mode (Nichols, 179-180), the semiotic storytelling techniques of non-fiction ecocinema (Ivakhiv, 12, 223), the Anticipatory Mode (Salazar, 44), and what I like to call the Direct Approach (Terry, 80). This documentary style involves working in collaboration with the policymaker before, during, and after production and presenting the finished film directly to them, showcasing the valued data they identified as being necessary for progressive environmental policy.

The component that seems most attractive to teachers, students, scientists, and policymakers alike is the documentary film element. Video is a great equalizer in communications as it presents visible evidence of research and thereby contextualizes concepts and data in written texts, providing a fuller understanding to the user of a Geo-Doc. Add to this the possibility of relationality between the film units, and the Geo-Doc becomes a useful tool in bridging the communication gap between science and policy as well as enhancing the pedagogy of environmental education.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

“Planetary Health Film Lab,” Dahdaleh Institute for Global Health Research. Toronto: York University, 2020. Web. Accessed April 30, 2020. Link: https://dighr.yorku.ca/projects/planetary-health-film-lab.

Ivakhiv, Adrian. Ecologies of the Moving Image: Cinema, Affect, Nature. Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2013b. Print.

Nichols, Bill. Introduction to Documentary. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2001a. Print.

Salazar, Juan Francisco. “Anticipatory Modes of Futuring Planetary Change in Documentary Film” in A Companion to Contemporary Documentary Film, ed. Alexandra Juhasz and Alisa Lebow. Oxford: Wiley, 2015. Print.

Terry, Mark. “Geo-Doc Creation Tips for Educators.” futurecinemaproject.com. Toronto: York University, 2020. Web. Accessed April 30, 2020. Link: https://futurecinemaproject.com/tip-sheets-2.

Terry, Mark. The Geo-Doc: Geomedia, Documentary Film, and Social Change. London: Palgrave MacMillan, 2020. Print.

GEO-DOC PROJECTS:

The Youth Climate Report GIS Project, creator, Mark Terry. Bonn, Germany: United Nations Climate Change, 2018. Web. Accessed April 30, 2020. Link: https://unfccc.int/news/see-inspiring-climate-action-entries-to-global-youth-video-competition.

Fast Fashion, creators (student names withheld). Toronto: York University, 2020 Web. Accessed April 30, 2020. Link: https://drive.google.com/open?id=1iyvxr3YFtZZG_ARpEIqWOUFZe97SFiOe&usp=sharing.

Mark Terry is an associate of the UNESCO Chair in Reorienting Education through Sustainability and Chair of the Advanced Disaster, Emergency and Rapid Response Simulation Arctic Group at York University in Toronto, Canada. He is also a documentary filmmaker and contract professor with the Faculty of Environmental Studies at York University in Toronto, Canada. He has worked with the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) since 2009.

Mark Terry is an associate of the UNESCO Chair in Reorienting Education through Sustainability and Chair of the Advanced Disaster, Emergency and Rapid Response Simulation Arctic Group at York University in Toronto, Canada. He is also a documentary filmmaker and contract professor with the Faculty of Environmental Studies at York University in Toronto, Canada. He has worked with the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) since 2009.

He has been decorated by Queen Elizabeth for this work with her Diamond Jubilee Medal and by The Explorers Club with its Stefansson Medal, the organization’s highest honour. The Academy of Canadian Cinema and Television gave him their rarely-presented Humanitarian Award for his unique contributions in bridging the gap between science and policy through film with the United Nations. His work in the polar regions earned him a place on Canadian Geographic Magazine’s Top 100 Greatest Explorers list in 2015.

Dr. Terry has given two TED Talks in Homer, Alaska, and the Ontario Science Centre on the subject of scientific discoveries in both the Arctic and Antarctica. He has also taught a Master Class in Arctic documentary filmmaking for the American Conservation Society’s 50th anniversary celebrations of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge and has lectured on polar filmmaking to aboriginal graduate students at the Arctic College of the Peoples of the North in St. Petersburg, Russia. Today, he teaches a course on ecocinema in the Faculty of Environmental Studies at York University’s Toronto and Costa Rica campuses.