By April Anson, Cassie Galentine, Shane Hall, Alex Menrisky, and Bruno Seraphin

Sometimes we wish we could solve the world’s problems with a *snap* of our fingers, even though we know it’s never that simple: compound problems require compound solutions. Still, accelerating climate crisis and the unwillingness of global leaders to take meaningful climate action can breed nihilism – likely we’ve all witnessed it in students, colleagues, family members, and even ourselves. With such nihilism, though, sometimes comes a notion that mass violence could be a viable environmental solution. This specter of ecofascism looms in pop-cultural imaginations as a malevolent threat for some and a tantalizing fantasy for others.

Case in point: Thanos, the arch-supervillain of the Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU). In 2018 and 2019 the character of Thanos appeared as the central villain in two of the highest grossing films of all time, Avengers: Infinity War and Avengers: Endgame. Thanos’ name is a wink to thanatos, the psychological death-drive. In the films, Thanos offers a simple message: mass murder will fix the world. Sounds like a creep, right? With a supercharged fingersnap, Thanos kills half the universe, believing that doing so will create prosperity for those left alive (spoiler: it doesn’t). Thanos’s plan doesn’t work because ecofascism never leads to improved environmental conditions. It merely entrenches the inequalities intrinsic to the economic and social relations responsible for climate change. Still, the MCU failed to address Thanos’s misleading mythology in a nuanced way, opting instead for a “good versus evil” final showdown. Thanos’s very real concerns about resource consumption were left unaddressed and, as a result, many viewers thought Thanos made some good points.

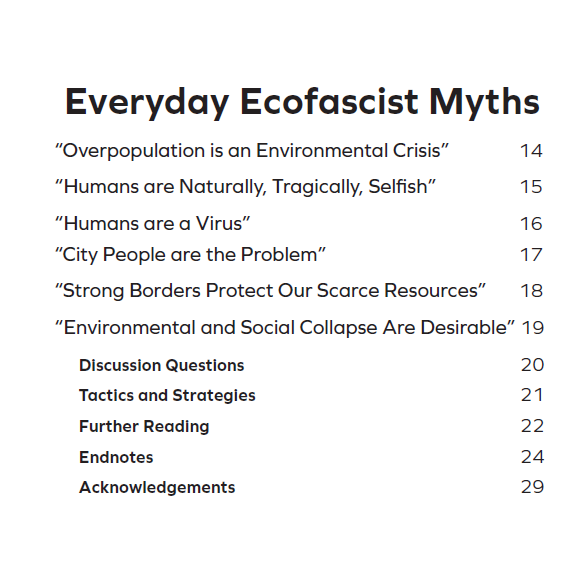

Such a high-profile ecofascist figure invites a response. The six of us, a group of scholars from universities across the United States formed the Anti-Creep Climate Initiative to expose and debunk the common ecofascist myths that circulate in our everyday lives. In partnership with graphic designer Melody Keenan, we created Against the Ecofascist Creep, a web zine and teaching resource that explores six “everyday ecofascist myths” and offers researched, concise essays (written for a general audience) that address the structural conditions of climate crisis and other environmental concerns. (The project takes inspiration for its name from Alexander Reid Ross’s fantastic 2017 book Against the Fascist Creep, which considers how fascist ideas “creep” into power not only via the far right, but also through mainstream and leftist channels.) For example, responding to Thanos, we engage the ecofascist argument that “overpopulation is an environmental crisis.” We trace the roots of its mythology to nineteenth-century imperialist fictions and eugenic race “science” and synthesize the extensive research that has disproved the premises and predictions of “overpopulation.”

The cover of Against the Ecofascist Creep, designed by Melody Keenan. The full zine is available via the button below and in ASLE’s Teaching Resources Database.

Against the Ecofascist Creep defines ecofascism as environmentalism that (1) Advocates or accepts violence and (2) Reinforces existing systems of power and inequality. Ecofascism suggests that certain kinds of people are naturally and exclusively entitled to control environmental resources. Though ecofascism is a slippery idea, ecofascist myths always fuel white supremacy, ultra-nationalism, patriarchy, ableism, authoritarianism, and mass murder. While some people proudly self-identify as ecofascists, others unintentionally repeat busted myths that support ecofascism. As a result, ecofascist myths creep into more progressive environmentalists’ rhetoric and efforts – and doom a real chance at a just, sustainable future. Our goal is to recognize and remove ecofascist ideas from the way we think and talk about the world.

Scholarship on ecofascism is catching up to the new threats that climate change poses for our political imaginations. Janet Biehl and Peter Staudenmaier cite the “Green Nazis” of the Third Reich as the origin of ecofascism, Jordan Dyett and Cassidy Thomas trace its expressions to the overpopulation discourse of American eugenicists, and many others read ecofascist ideologies in the twentieth and twenty-first century U.S.—in, for example, deep ecology’s charge to “save the planet, kill yourself,” Earth First!’s publication of the question “Is AIDS the answer to an Environmentalist’s Prayer?,” and the xenophobia trucked in through tales of apocalyptic population bombs and tragic, tautological stories of the commons. Drifting from its derogatory association with leftist movements, the moniker of ecofascism is now increasingly claimed through the self-referential intellectualism of far-right terrorism – a dramatic reversal of the climate denial long associated with right-wing politics.

Table of Contents from Against the Ecofascist Creep.

As Anti-Creep Climate Initiative member April Anson makes clear, the roots and routes of ecofascism extend much earlier, to the beginnings of U.S. racial capitalism and settler colonialism. Ecofascist ideas animate the land logics of John Locke, who provided American environmental thinking with fantasies of “wasted,” “uncultivated,” and “empty” land through which to narrate the genocidal logics of colonial capitalism. They harmonize with the white supremacist notes of Thomas Jefferson’s romantic agrarianism. They ground the beloved “origin” of American environmental thinking, Ralph Waldo Emerson, as the “philosopher king of American white race theory” (as Nell Irvin Painter names him in The History of White People). While American eugenicists like Teddy Roosevelt are commonly cited in ecofascist genealogies, they built on a long tradition tied less to swiftly shifting national boundaries or fickle political affiliations than to the circulation of a narrative tradition where violence is a part of the “natural” order of people and planet. The climate crisis clarifies ecofascism not so much as a matter of left versus right, but as a broadly circulating appeal to “nature” and “natural law” that creeps across political and national identities and geographic and imaginative borders.

Against the Ecofascist Creep fights this rhetoric – a project especially relevant in light of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, which has reinvigorated ecofascist strategies such as blaming immigrants, people of color, and impoverished individuals for environmental damage. We have seen (and continue to see) a rise in anti-Asian hate crimes and deployment of many of these ecofascist myths to racialize disease and justify mass death, ignoring the way minoritized communities are more likely to suffer from COVID as well as experience environmental injustice. Not all people contribute equally to climate change, nor do we all experience its impacts equally. Ecofascism’s co-optation of environmental rhetoric requires the erasure of both the industrial polluters responsible for most historic and ongoing emissions and the experiences of historically marginalized communities, especially Black and Indigenous voices and modes of community survival and resistance.

The first page of the opening comic, which presents an alternate response to Thanos’s ecofascism.

Ecofascism, like fascism, never springs from nowhere. It creeps through our language, metaphors, visual media, narratives, and ideas of environmental health and security. Though Thanos believed he was helping solve real problems, he became part of the problem. His philosophies continue to normalize ecofascist ideas in our everyday life. This zine is intended to be a tool to help halt ecofascism wherever, whenever it may be creeping, by examining its roots, prompting reflection, and inspiring action.

The Anti-Creep Climate Initiative smashes ecofascist mythology, champions liberatory environmental futures, and has fun doing it! The Initiative was formed by April Anson, Cassie Galentine, Shane Hall, Alex Menrisky, and Bruno Seraphin. April Anson is an Assistant Professor of Public Humanities at San Diego State University, core faculty for the Institute for Ethics and Public Policy, and affiliate faculty in American Indian Studies. Cassie Galentine is a doctoral candidate in English at the University of Oregon. Shane Hall is an Assistant Professor of Environmental Studies at Salisbury University. Alex Menrisky is an Assistant Professor of English and affiliate faculty in American Studies at University of Connecticut. Bruno Seraphin is a doctoral candidate in sociocultural Anthropology at Cornell University, with a graduate minor in American Indian and Indigenous Studies.